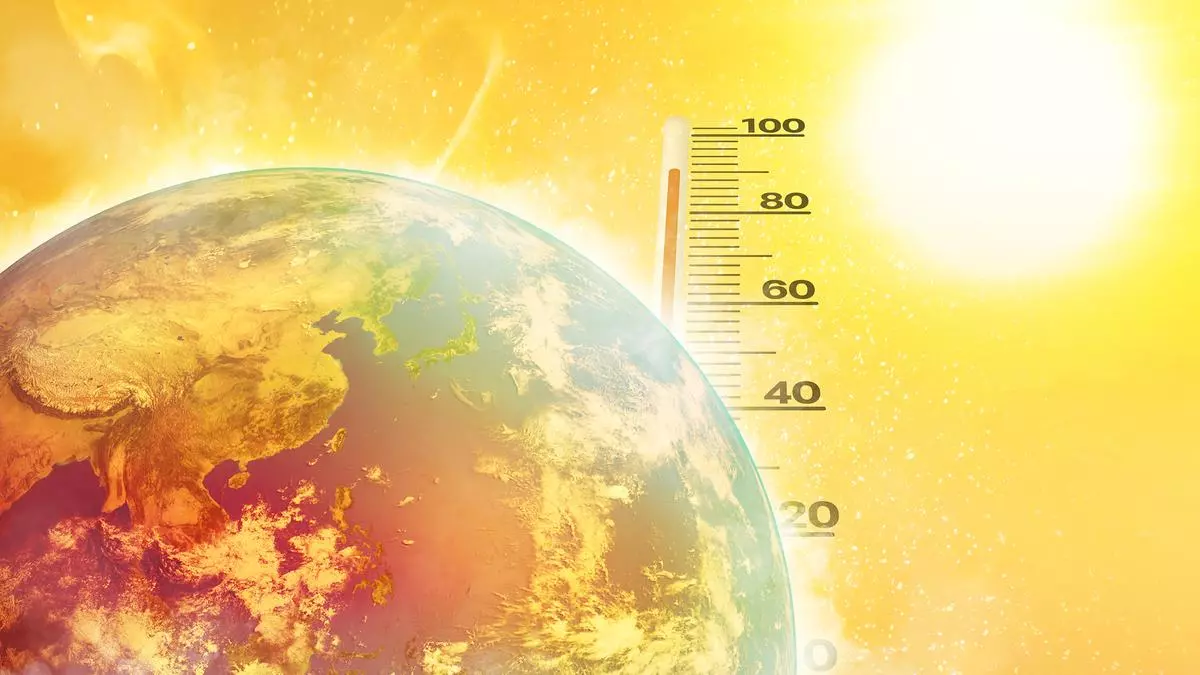

Killer heatwaves are caused by high temperatures, which, as is well known now, are a result of global warming. But there is a worse type, which a group of researchers have named ‘oppressive heatwaves’, triggered by a combination of high temperature and high humidity. The researchers, from IIT-Bombay and ETH Zurich, warn that oppressive heatwaves are likely to occur more frequently — so, be prepared.

‘Heatwaves’ are defined in terms of temperature exceeding a certain threshold for a specified period (days). The India Meteorological Department (IMD) defines a heatwave as three or more days with a temperature exceeding a predetermined threshold based on topography (namely above 45 degrees C in plains and above 40 degrees C in hilly areas).

The researchers examined the historical changes in heatwave characteristics and their association with human mortality in India. Given the importance of humidity in heatwave estimation, and that India experiences high humidity due to its geographical location, they classified heatwaves into oppressive (high temperature and high humidity) and extreme (high temperature and low humidity). They further examined the likelihood of future heatwave events following global warming by 1.5 degrees C and 2 degrees C, relative to the pre-industrial period, using daily maximum temperature, daily mean temperature, and specific humidity simulations from the Community Earth System Model Large Ensemble Numerical Simulation (CESM-LENS) data set.

They used the IMD’s daily temperature data at 1-degree spatial resolution and data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Centre for Environmental Prediction (NCEP), and National Centre for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), from 1951 to 2013.

They projected the ‘oppressive heatwave’ days and ‘extreme heatwave’ days for the near future (2035-65) and the far future (2070-2100) to understand the changes in heatwaves during these two time periods relative to historical climate (1975-2005).

Then they examined the association of heat-related mortality with oppressive and extreme heatwave days from 1967 to 2007 — because there is reliable data for this period.

“The heat-related mortality is strongly positively related to oppressive heatwave days relative to dry heatwave days,” the researchers say in a paper that awaits peer review.

“Since oppressive heatwave days significantly increase over India in most climatologically homogeneous zones, we infer the exacerbated heat-related mortality in the future if such heatwave conditions increase monotonically in the future, as these have been in recent decades,” the paper says.

Five-fold increase

The paper examines the situation under two scenarios of global warming — a rise in global temperatures by 2 degrees C; and by 1.5 degrees C.

“Our results show a five-fold increase in the number of days of oppressive heatwaves under 1.5 degrees C warming in both mid (2035-2065) and end (2070-2100) of the 21st century, relative to the historical period (1975 to 2005), whereas the number of extreme heatwave days remains relatively constant in mid and end of this century,” it says.

As for 2 degrees C warming, it would result in an eight-fold increase in the number of days of oppressive heatwaves by the end of the century, relative to the historical period and 1.5 degrees C warming conditions.

“These results suggest that limiting the mean global warming to 1.5 degrees C can reduce the likelihood of oppressive and extreme heatwaves by 44 per cent and 25 per cent by the end of the century, relative to the 2-degree C warming world,” says the paper, authored by Naveen Sudharsan, Subimal Ghosh and Subhankar Karmakar of IIT-Bombay, and Jitendra Singh of ETH Zurich.

“The remarkable increase in oppressive heatwave days highlights the elevated risk of heatwaves over densely populated countries and indicates an imminent need for adaptation measures,” it warns.

SHARE

- Copy link

- Email

- Facebook

- Telegram

- LinkedIn

- WhatsApp

- Reddit

Published on January 26, 2025