Advanced robotic surgery allows for faster recovery for patients in cancer treatment, even as it helps cut overall healthcare costs.

Conventional surgery often results in substantial physical trauma, while robotic methods help minimise this trauma. “This helps reduce the body’s stress response and quickens recovery,” says Dr Venkat P, a member of the Veritas Cancer Care team who is also associated with Apollo Cancer Centre.

For example, conventional open surgery for colorectal cancers typically requires hospital stay of 7-9 days, followed by about a month of recovery at home. Robotic surgery reduces this to just two days in hospital and about one week at home, according to the Veritas Cancer Care team, led by Dr Venkat and Dr Priya Kapoor.

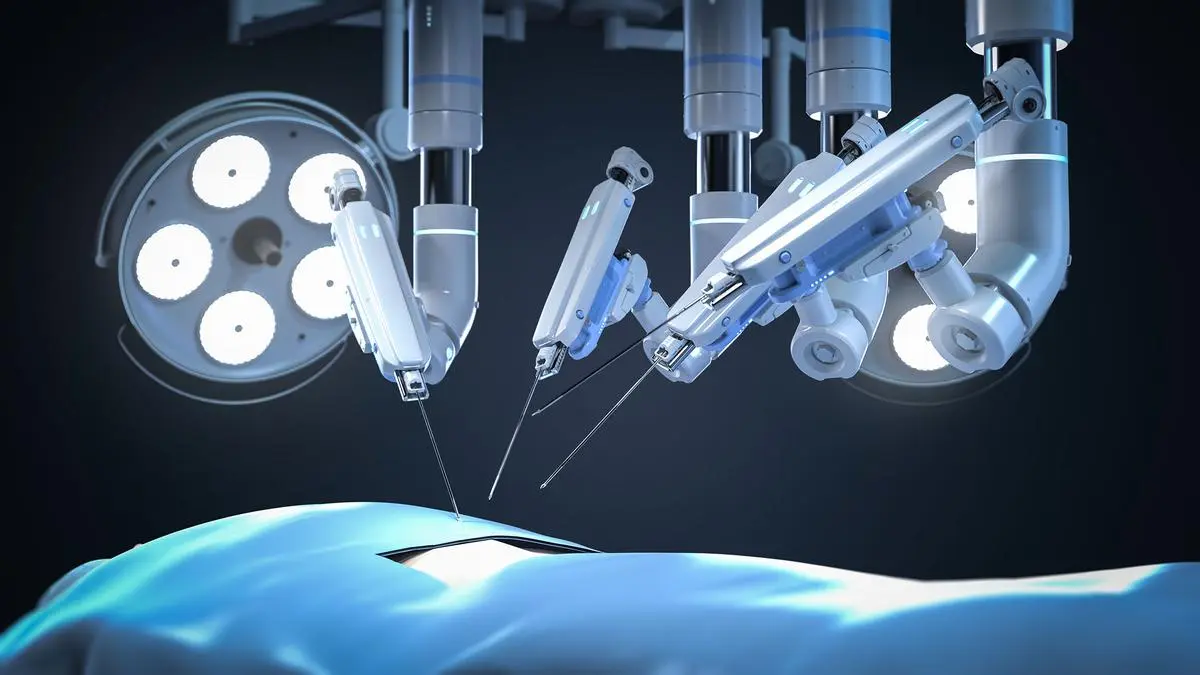

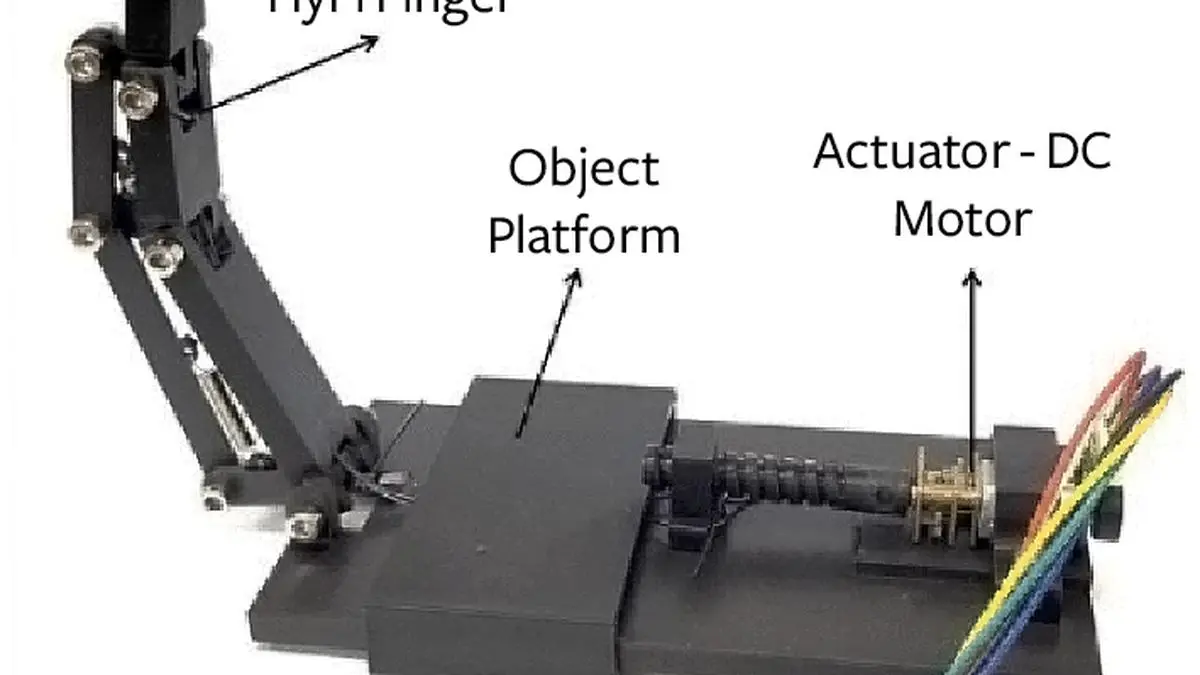

Here’s how it works: robotic surgery requires the surgeon to manoeuvre the instruments from a console that is at a distance from the patient.

Dr Venkat says the team pioneered the robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy in the country in November 2023. It has 58 cases under its belt, he says, among the highest across the country. This is an important option for young patients anxious to retain an aesthetic appearance after surgery. Using robotics to remove muscle and skin from the patient’s back for breast reconstruction results in smaller scars, reduced tissue trauma and faster recovery.

The team also performed the first robotic cytoreductive surgery for complex ovarian cancers. Combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy or HIPEC, the procedure helps significantly improve outcomes. HIPEC is a surgical procedure in which heated chemotherapy drugs are directly circulated into the abdominal cavity after cancer tumours have been surgically removed.

This treatment is used for advanced abdominal cancers like those in the appendix, colon, stomach, and ovaries, as the heat increases the drugs’ ability to penetrate cancer cells while reducing side effects.

The team also conducted Tamil Nadu’s first robotic surgery for thyroid cancers. Dr Venkat explains that there is no scar in the neck, and only a small keyhole scar in the underarm for improved cosmetic appeal.

The Veritas team has also conducted complex ‘Whipple surgeries’ using robotic methods. The Whipple technique is a complex surgery for pancreatic cancer involving the removal and reconnection of the pancreas, stomach, and bile duct. Dr Kapoor says, “We have performed at least 28 Whipple surgeries.”

But doesn’t robotics involve high investment, thereby raising the overall costs for the patient? Dr Kapoor agrees but points out that “shorter hospital stays and lower risk of complications, such as wound infections, help lower the need for expensive post-operative care and medicines. For patients who are working, returning to their workplaces earlier adds to the long-term benefit. Likewise, for those who travel to a different city for the surgery, shorter hospital stays brings down associated expenses.

But not all cancers can be removed using robotic methods. ‘Surgical selection’ remains paramount, she emphasises. Keyhole surgery cannot help in the case of complex, large tumours (for instance, an ovarian mass measuring 30 cm). As the tumour must be removed whole in such cases, too, a large incision may be needed, whether or not robotic methods are used.

Robotic ‘telesurgery’?

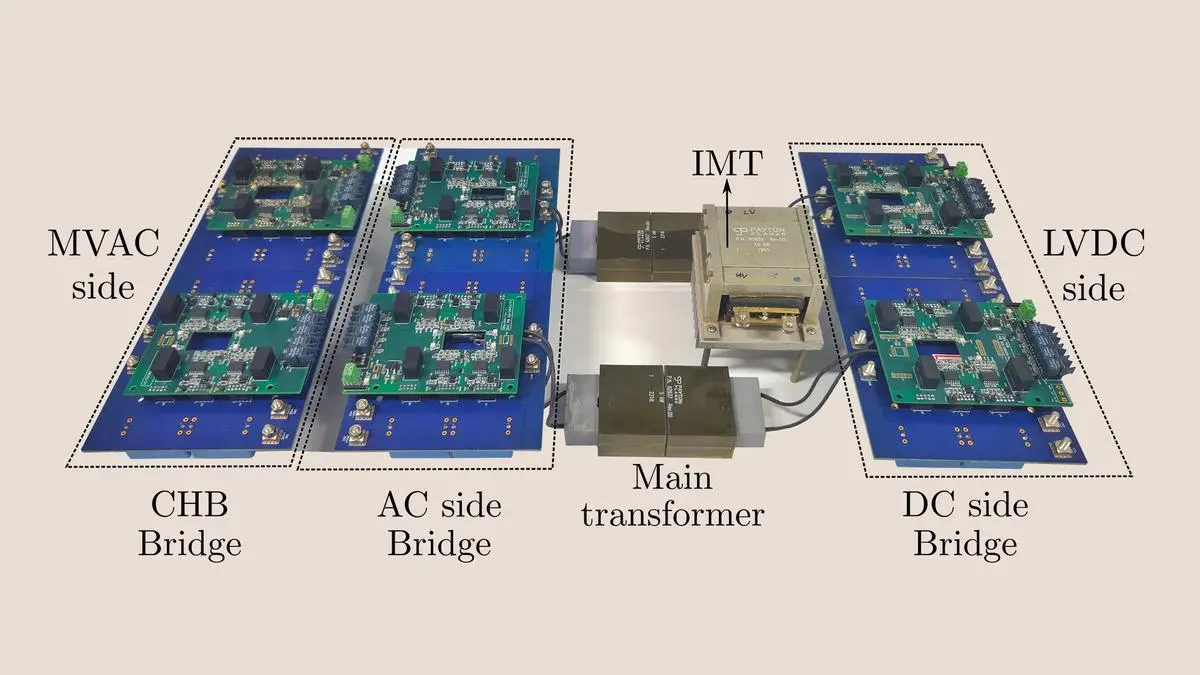

Telesurgery, or remote robotic surgery — where the surgeon operates from a distance — is possible and has been demonstrated through trans-Atlantic cardiac surgeries several years ago. However, says Dr Kapoor, it’s not a regular feature in complex cancer surgeries as it would need two equally skilled surgical teams at both ends, as well as extensive engineering support. This is critical in case the telecom signal is lost mid-surgery or if there is some malfunction in the robotic platform.

She also points to ethical issues surrounding such an operation where the surgeon is not present in the same location as the patient. She says the most practical and ethical application of telesurgery is in the training and mentoring of other robotic surgeons — where the mentee surgeon performs a surgery, while the mentor monitors and guides from another location.

More Like This

Published on October 20, 2025